In preparation for the release of director Terrence Malik’s highly anticipated documentary, Voyage of Time, Sciren Gia Mora had a chance to speak with science advisor Andrew Knoll, Harvard professor and author of The Evolution of Primary Producers in the Sea and Life on a Young Planet.

Gia Mora: Thank you so much for meeting with me. First of all, congratulations. I saw the film last week here in Los Angeles, and I was really awestruck.

Andrew Knoll: I’m glad you were. Congratulations shouldn’t go to me–they should really go to Terry [director Terrence Malick] and his vision, but I’m glad you like it. I think it’s amazing.

GM: It absolutely is. I didn’t quite know what to expect going into it, but from the first moment sitting in the IMAX theatre, it’s really visually overwhelming in a good way. It makes you feel small and connected at the same time. That’s a huge feat to accomplish.

AK: Well, I’m glad to hear you say that because I think Terry would be very pleased by that reaction. I think what he wants is for all of us to consider that we’re the product of this nearly 14 billion year history, and that’s a rather large thought.

GM: I read in the press materials that you believe in a “dynamic give and take between the romance of art and the rigorousness of scientific pursuit.” So I’m curious, as the science advisor on the film, do you think this film strikes the right balance between art and scientific rigor?

AK: I think it does. My job really was simply to help Terry to get the science right, and I’m quite satisfied that the science is pretty faithfully depicted in the movie. And at the same time, it’s not the way that someone like me would tell the story. It’s a much more abstract and philosophical take, but I think that’s something good because we can watch NOVA every week on PBS, but how 0ften do you get an artist saying, “Here’s my take on it.” I think it’s true for this.

GM: It’s funny to hear you talk about NOVA because that’s, I think, my primary interaction with a story like this.

AK: They do a great show. NOVA is very good at what they do, and what I find so fascinating about Voyage of Time is that it actually does something else.

GM: Yeah, absolutely. You’re known for your willingness to contemplate the unknown, so I think that a new format like this suits you quite well. I’d like to know a little bit more about how creativity and creative problem-solving play into your work both on the film and as a scientist and writer.

AK: Well, I think that, you know, anyone–whether you’re a scientist or a filmmaker or a writer or a musician or an artist–I think curiosity is extremely important. I can’t imagine being a scientist without being curious about everything around me. And I’m not sure that I can define creativity, much less claim it for myself, but I think that the job of the scientist, just like the job of the artist, is to make something where there was nothing before. And that takes a combination of curiosity and discipline and knowledge. And maybe creativity is what happens when all those things come together.

GM: I love that! How do you see advising a project like Voyage of Time versus advising something going on at JPL or NASA that you’ve worked on? Do you think that they’re more similar than they are different–does that creative process work in the same way when you’re working in these different capacities? Or are they very, very different?

AK: I think it probably depends on what axis you evaluate them. Really, I have always been struck by the creativity of the engineers at JPL. They are creative people in as full a sense as Terry Malik is a creative person. They’re just creative in different ways. I would just count myself lucky to be able to get to know both of them.

GM: Absolutely. When you began studying science, did you ever imagine that you’d find yourself working with a filmmaker like Terrence Malik? That a large culmination of your time would all of a sudden come into something so different from what you originally set out to do?

AK: No, not at all. It’s just good luck, and I am just grateful that Terry asked me to work with him. That lead to some very good moments in my life.

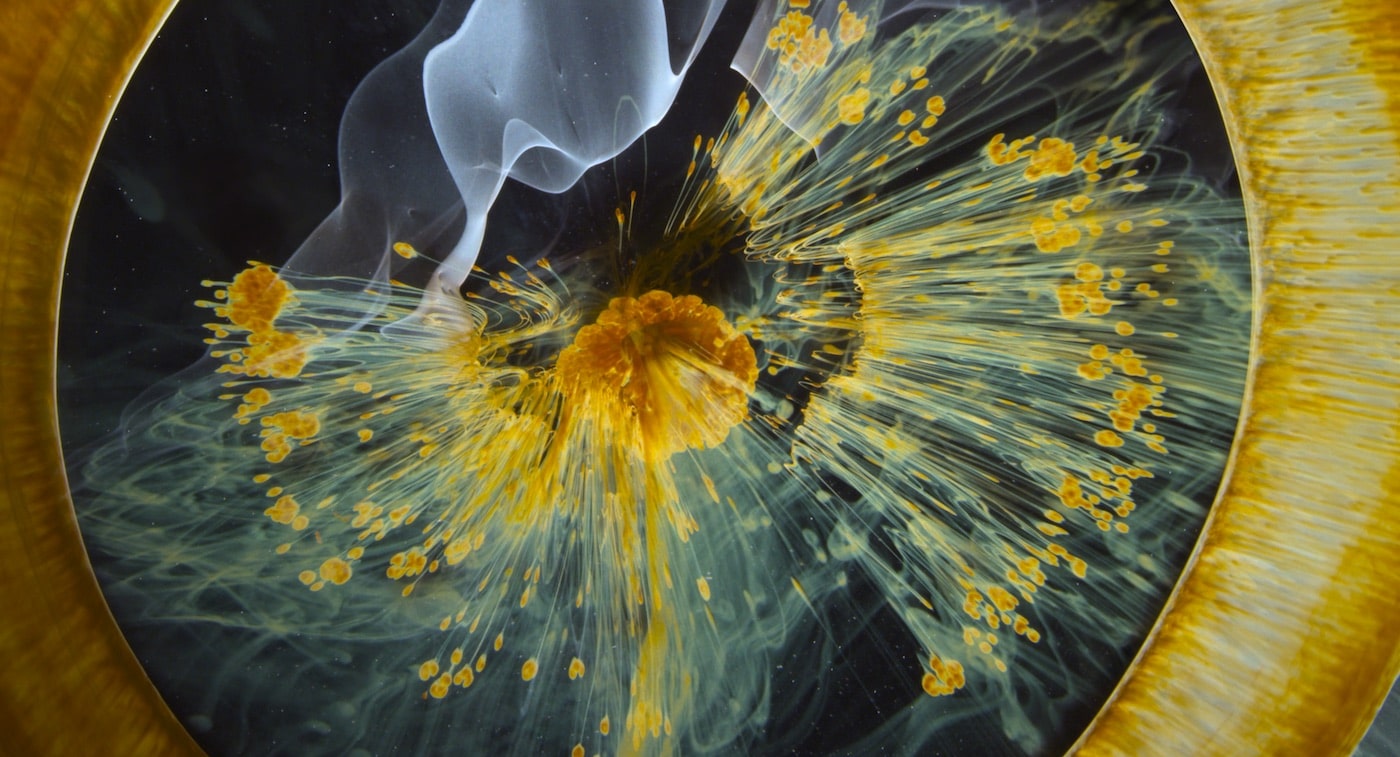

GM: I have a very personal question for me. I’m concerned about climate change and how we discuss it, especially in entertainment. And in the press materials, it says that “the very patterns of life generating, struggling, evolving and thriving … speak to us, even inspire us, in the here and now.” And the primary conflict of the film is nature versus nature. From that first moment when one cell eats another cell, and we watch that sort of struggle, we see this sort of binary life-and-death kind of conflict happening again and again and again. How can a film like this “inspire us in the here and now” on the precipice of global climate change, and how can we use entertainment in a way to engage in a conversation about that?

AK: That’s a good question. You know, Voyage of Time has very little that addresses things like climate change, but it does have a little vignette at the end when the Sun becomes a supernova, and that’s it for the planet, but less about the 21st century. But that said, I think that people will be inspired to take action on things like global [climate] change if they understand the planet to begin with, and so I think that what the film does tell us is that the world that we inherited is 14 billion years in the making, and we’re the stewards. So what happens to the product of that history is really up to us, and I would hope that that understanding would spur people into positive action.

GM: Indeed. How much did Mr. Malik’s film change once you became involved with it? I understand that you and he spoke a great deal at length before anything even began to be made. Is that correct?

AK: Yeah, I mean it’s obviously an iterative process. You know, over the years–and this really was years in the making–I saw a number of scripts. And Terry and I would talk about, “If you have 45 minutes to tell the story, and that story is 14 billion years long, [laughing] how do you pick and choose?” So it was fascinating to me to see what he chose and how he chose to depict the science that he did. Again, it’s fascinating to me–I’ve seen several iterations of the IMAX film over the last year or so, again just fascinating from the technical sense to see how does he tweak it between versions. So to me, it’s just fascinating in the same way that it’s fascinating to go to Colonial Williamsburg and look at a carpenter. You know, just the craft involved.

GM: Sure. It cracks me up to think of a script for this–the descriptive paragraphs that must have existed to describe what visuals we’re seeing! [laughing]

AK: [laughing] Well, yeah!

GM: As an actor, I spend my life looking at scripts, and I can’t even fathom what you must have seen. That sounds incredible.

AK: Well, it was fun. Again, it went from things that were sort of canonically scientific to extremely abstract philosophical things. There’s two narratives for the IMAX film, and I don’t know which you saw. Both versions are narrated by Brad Pitt. One of them is geared toward school children–high schoolers and that–and it is more straight forward in describing science, and the other is more philosophical.

GM: We most certainly saw the philosophical one because one of my thoughts was, “I can’t imagine being a high schooler and not having probably a decent grasp of these bigger concepts to know how to put it into context.”

AK: I will tell you that the first time I ever saw a preliminary version of the film, my first comment to Terry was, “If I didn’t know the story coming into this, would I be able to piece it together from the film itself?” And he has moved much toward giving the viewer clues as to what’s going on. And I should say too that there is–under Terry’s active support and guidance–an educational website going up that will, for example, show some of these vignettes, and then have a prominent astrophysicist explain what’s behind them and that. So Terry is concerned that this becomes educational and not just inspirational. And I think that website will be probably helpful to a lot of people who are curious about the movie.

GM: Oh, I think so. Although I have to say the poetry of it is really quite profound as an artistic expression. Between the soundtrack and the narration and the visuals, really it is sparse and overwhelming all at the same time, much like poetry can be, where you’re bombarded with images, and those images are so lasting that, if nothing else, certainly the inspiration is one thing that will drive you toward the education so that you understand what you’ve just seen.

AK: I think that’s right–I agree with you completely. And I think Terry’s decision not to simply have someone like David Attenborough say, “And then the dinosaurs came in the Triassic period.” That was why. You can get the science, the facts, in a lot of places. You can’t get this artistic vision anywhere else.

GM: That seems true to me. Well, what a pleasure to speak with you. Thank you so much for your time today, and congratulations again to you and everyone involved in the project.

AK: Great. Thanks a lot.

Special thanks to Brian Boothe for arranging this interview.