The young lady waited patiently. Whether she was the daughter of a VIP or she was just so adorable that a savvy PR flack snagged her from the general admission line was unclear, but one thing was certain: Dr. Jane Goodall was her hero.

The girl’s fair coloring, low ponytail, and jungle khakis made her nearly indistinguishable from the images of 26-year-old Goodall pictured behind her on the “yellow” carpet. When Dr. Goodall had politely stepped away from the throngs of hungry reporters, Mini-Me Jane stepped forward and offered up a vintage National Geographic cover for Goodall to sign, a stuffed chimpanzee clutched in her other hand.

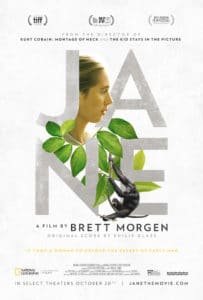

The girl and Goodall herself were there to celebrate the opening of Brett Morgen’s beautiful documentary, Jane—a film which will surely inspire an entirely new generation of Mini-Me Janes to jump on the next plane to Gombe. The film is a love letter to Goodall’s singular vision and her complimentary, if not at times contentious, relationship with her late husband Hugo van Lawick.

Had I been a child at the Hollywood Bowl last week, watching 18,000 people give a female scientist with no formal training a standing ovation, I would have been enthralled by the adventure, the bravery, and the fierce independence that define Goodall, even into her 80s. As an adult, I felt a sense of camaraderie and empowerment–despite the current political climate, I was surrounded by thousands of people who applauded this woman for the trailblazer she is. I felt like there was a chance for us all to help save the planet, and that agency gave me a sense of relief that not all hope was lost.

Had I been a child at the Hollywood Bowl last week, watching 18,000 people give a female scientist with no formal training a standing ovation, I would have been enthralled by the adventure, the bravery, and the fierce independence that define Goodall, even into her 80s. As an adult, I felt a sense of camaraderie and empowerment–despite the current political climate, I was surrounded by thousands of people who applauded this woman for the trailblazer she is. I felt like there was a chance for us all to help save the planet, and that agency gave me a sense of relief that not all hope was lost.

The quieter moments of the film, however, provoked an entirely new set of questions I’d never have considered as a child and certainly did not anticipate being raised in the film. Much ink is spilled discussing whether women can indeed “have it all,” and a woman as accomplished as Goodall should certainly serve as proof that we can. But Goodall is too smart to be reduced to an aphorism. The several days of interviews she gave to Morgen reveal a struggle I hear rioting inside all my ambitious female friends: How can I be a dedicated attorney/artist/activist and support my spouse’s ambitions, all while raising my child myself?

For Goodall, and many women around the world, something (or things) had to give. When her son was small, she shifted her focus from studying the parenting skills of chimps to employing her own parenting skills. Only when her son, aptly nicknamed Grub, left for school could she refocus on her career, and even then she wasn’t as involved with the animal interaction as she was with administering the ins and outs of her research center. At the same time, her husband–still considered one of the finest wildlife filmmakers and photographers of all time–was eager to pursue his own career, and when she declined to follow him, that too ended. Divorced, her child in boarding school thousands of miles away, Goodall resumed the kind of work she’d done as a very young woman alone in the jungle. That, she says, is when she returned to homeostasis.

Make no mistake–this movie is a love story, just not one that ends on a Disney-like kiss between the happy couple. This is about the love of work and how it defines who we are. Goodall’s fidelity supersedes the quotidian activities most of us live for. For more than 30 years, she has worked tirelessly to save the planet, never spending more than three weeks in one place. Her dedication to conservation as well as animal and human rights prove that she’s made of something different, something that puts her in the ranks of Gandhi and Martin Luther King. These visionaries give completely of themselves for a greater cause, and the world is a better place for it. But for those who are intricately involved in the lives of such great thinkers, the emotional toll is steep.

Examining a work of art says as much about the art as it does about the viewer, and clearly much of this essay speaks to the questions currently swirling around in my brain, not least of which is wondering whether my (as of yet unborn) children will understand that chimpanzees and elephants and tigers and rhinos are not just imaginary characters memorialized in The Jungle Book. If there’s one hope Goodall has for this film, it is that her message of conservation spreads as quickly and ferociously as any Facebook fake news headline. Morgen’s extraordinary pacing, aided by Philip Glass’s mesmerizing score, greatly help this cause. When I saw Morgen’s last film Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, I got the feeling that Morgen wished he could have been there with Cobain, that perhaps if Morgen had been there, Cobain just might still be alive. In seeing Jane, I got the feeling that he wanted not just to be there with Goodall but to become her, to see the world as clearly as she did. And although the majority of the visuals in the film come from van Lawick’s eyes, it’s the closest thing we have to a Being John Malkovich view inside Goodall’s head. Hugo loved Jane, and their simpatico allows us, these five decades later, to see what she saw and to become as enchanted as she is with the natural world.

To see Goodall on stage and to hear Glass’s score performed live by a 78-piece orchestra is a once in a lifetime gift, but perhaps even more special was the moment when the son of a red carpet attendee snagged the microphone from the Italian news reporter, blurting out, “Jane’s the best! Living in the jungle–with the monkeys!” May we all be filled with such joy, passion, and desire to make a difference.

Jane is now playing in select theatres.